Aproximação linear para duas variáveis: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "Aproximar uma função de duas variáveis com um plano tangente é a extensão natural do mesmo conceito para funções de uma variável. Da mesma forma que ampliando bastante um gráfico de uma função de uma variável o faz ser renderizado quase como uma reta. O mesmo acontece com curvas de nível de uma função de duas variáveis. As curvas de nível se aproximam de linhas retas paralelas se ampliarmos bastante. <div style="text-align:center;"> image:linear_appro...") |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Uma função de várias variáveis precisa ser contínua e diferenciável para permitir a aproximação do plano tangente. No caso da função ser contínua mas não diferenciável um plano existe, mas não será o plano tangente procurado porque se a função não é diferenciável não pode existir um plano tangente. Por exemplo: <math>f(x,y) = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}</math>. Um plano em <math>(0,0)</math> não será horizontal. Será inclinado numa direção ou outra. | |||

== | ==O plano tangente== | ||

Na geometria analítica um plano é definido com <math>Z = O + t_1\overrightarrow{v_1} + t_2\overrightarrow{v_2}</math>. Na forma vetorial cada ponto é dado por um ponto origem, dois parâmetros e dois vetores linearmente independentes. Na forma geral temos uma equação que deve ter sido vista em algum momento na escola: <math>Ax + By + Cz + d = 0</math>. | |||

Assumindo que a função seja diferenciável num ponto, temos que: | |||

<math>f(x_0,y_0)</math> | <math>f(x_0,y_0)</math> o ponto origem | ||

<math>(x - x_0)</math> | <math>(x - x_0)</math> e <math>(y - y_0)</math> dois pares de pontos, pertencendo ao domínio da função, que dão a direção em <math>x</math> e em <math>y</math>. | ||

<math>\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)</math> | <math>\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)</math> e <math>\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0)</math> as variações em cada direção, que correspondem a <math>t_1</math> e <math>t_2</math> na forma vetorial. | ||

Portanto, a equação do plano tangente é: | |||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Com esta equação achamos todos os pontos do plano tangente. Ignoramos o <math>d</math> porque este plano não é qualquer plano, mas um que esta atrelado à função de duas variáveis. | |||

== | ==A reta normal== | ||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

[[image: | [[image:normal_line_pt.png|400px]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Na geometria analítica podemos provar que <math>ax + by + cx = 0</math>, o vetor <math>(a,b,c)</math> é perpendicular ao plano. Podemos fazer o mesmo para o plano tangente e obter o mesmo vetor da equação do plano tangente. Olhando na equação anterior, obtemos: | |||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

''' | '''Vetor normal:''' <math>\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0), \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0), -1\right)</math> | ||

''' | '''A forma vetorial da equação da reta é então:''' <math>\overrightarrow{r} = (x_0,y_0,f(x_0,y_0)) + t\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0), \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0), -1\right)</math> | ||

Na geometria analítica aprendemos que o '''produto escalar''' de dois vetores perpendicular é zero. Portanto: | |||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Alguém pode ter pensado sobre o gradiente, porque o gradiente é perpendicular à curva de nível. Isto dá origem à pergunta: '''Pode o gradiente ser paralelo à reta normal?''' Para que isto aconteça o plano tangente precisa ser tangente à superfície de nível, não à própria superfície da função. Pode um plano ser tangente à uma curva de nível e à função ao mesmo tempo? Isto é impossível porque as curvas de nível são paralelas ao eixo XY. O plano tangente teria que ser vertical. Porém, o gráfico de uma função de duas variáveis não pode ter curvas de nível empilhadas ou sobrepostas. | |||

Latest revision as of 21:19, 23 August 2022

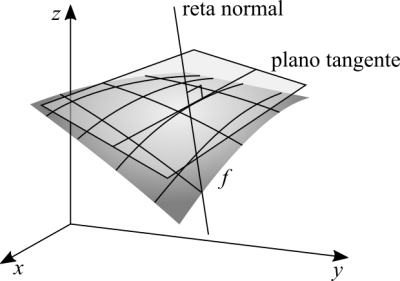

Aproximar uma função de duas variáveis com um plano tangente é a extensão natural do mesmo conceito para funções de uma variável. Da mesma forma que ampliando bastante um gráfico de uma função de uma variável o faz ser renderizado quase como uma reta. O mesmo acontece com curvas de nível de uma função de duas variáveis. As curvas de nível se aproximam de linhas retas paralelas se ampliarmos bastante.

Uma função de várias variáveis precisa ser contínua e diferenciável para permitir a aproximação do plano tangente. No caso da função ser contínua mas não diferenciável um plano existe, mas não será o plano tangente procurado porque se a função não é diferenciável não pode existir um plano tangente. Por exemplo: [math]\displaystyle{ f(x,y) = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} }[/math]. Um plano em [math]\displaystyle{ (0,0) }[/math] não será horizontal. Será inclinado numa direção ou outra.

O plano tangente

Na geometria analítica um plano é definido com [math]\displaystyle{ Z = O + t_1\overrightarrow{v_1} + t_2\overrightarrow{v_2} }[/math]. Na forma vetorial cada ponto é dado por um ponto origem, dois parâmetros e dois vetores linearmente independentes. Na forma geral temos uma equação que deve ter sido vista em algum momento na escola: [math]\displaystyle{ Ax + By + Cz + d = 0 }[/math].

Assumindo que a função seja diferenciável num ponto, temos que:

[math]\displaystyle{ f(x_0,y_0) }[/math] o ponto origem

[math]\displaystyle{ (x - x_0) }[/math] e [math]\displaystyle{ (y - y_0) }[/math] dois pares de pontos, pertencendo ao domínio da função, que dão a direção em [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] e em [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0) }[/math] e [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0) }[/math] as variações em cada direção, que correspondem a [math]\displaystyle{ t_1 }[/math] e [math]\displaystyle{ t_2 }[/math] na forma vetorial.

Portanto, a equação do plano tangente é:

[math]\displaystyle{ z - f(x_0,y_0) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)(x - x_0) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0)(y - y_0) }[/math]

Com esta equação achamos todos os pontos do plano tangente. Ignoramos o [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] porque este plano não é qualquer plano, mas um que esta atrelado à função de duas variáveis.

A reta normal

Na geometria analítica podemos provar que [math]\displaystyle{ ax + by + cx = 0 }[/math], o vetor [math]\displaystyle{ (a,b,c) }[/math] é perpendicular ao plano. Podemos fazer o mesmo para o plano tangente e obter o mesmo vetor da equação do plano tangente. Olhando na equação anterior, obtemos:

[math]\displaystyle{ z = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)(x - x_0) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0)(y - y_0) - f(x_0,y_0) }[/math]

Vetor normal: [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0), \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0), -1\right) }[/math]

A forma vetorial da equação da reta é então: [math]\displaystyle{ \overrightarrow{r} = (x_0,y_0,f(x_0,y_0)) + t\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0), \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0), -1\right) }[/math]

Na geometria analítica aprendemos que o produto escalar de dois vetores perpendicular é zero. Portanto:

[math]\displaystyle{ [(x,y,z) - (x_0, y_0,f(x_0,y_0))] \cdot \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0), \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0), -1 \right) = 0 }[/math]

Alguém pode ter pensado sobre o gradiente, porque o gradiente é perpendicular à curva de nível. Isto dá origem à pergunta: Pode o gradiente ser paralelo à reta normal? Para que isto aconteça o plano tangente precisa ser tangente à superfície de nível, não à própria superfície da função. Pode um plano ser tangente à uma curva de nível e à função ao mesmo tempo? Isto é impossível porque as curvas de nível são paralelas ao eixo XY. O plano tangente teria que ser vertical. Porém, o gráfico de uma função de duas variáveis não pode ter curvas de nível empilhadas ou sobrepostas.