Gráficos da parábola, exp e log: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "Para entender poque o gráfico é uma linha reta ou uma curva você não precisa entender cálculo, mas você precisa entender a tangente. Esta página tem por objetivo dar uma ideia bastante superficial dos gráficos. Não vou discutir pontos de inflexão, pontos críticos ou derivadas aqui. Tudo que você precisa entender para marcar um ponto de uma função no plano cartesiano é entender que cada ponto é um par ordenada da forma <math>(x, \ f(x))</math>, com <math>...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Dependendo de qual difícil é traçar gráficos à mão para você, gráficos muito distorcidos podem muito bem levar à interpretações incorretas. Não sei se há professores muito pedantes quanto à "corretude" dos gráficos. Aqui eu comentaria sobre linhas retas x curvas. Algumas pessoas podem ter dificuldade com um ou outro e pode ter relação com a coordenação motora ou algo assim. Mas há tambem uma questão de perfeccionismo onde algumas pessoas podem relacionar a interpretação de alguns problemas de modo muito forçado a um gráfico exageradamente correto. | Dependendo de qual difícil é traçar gráficos à mão para você, gráficos muito distorcidos podem muito bem levar à interpretações incorretas. Não sei se há professores muito pedantes quanto à "corretude" dos gráficos. Aqui eu comentaria sobre linhas retas x curvas. Algumas pessoas podem ter dificuldade com um ou outro e pode ter relação com a coordenação motora ou algo assim. Mas há tambem uma questão de perfeccionismo onde algumas pessoas podem relacionar a interpretação de alguns problemas de modo muito forçado a um gráfico exageradamente correto. | ||

== | ==A parábola== | ||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Você já se perguntou por que <math>f(x) = x^2</math> é uma parábola? Se <math>f(x) = x</math> é uma linha reta, como elevar ao quadrado muda tanto? Eu vou recorrer a um raciocínio puramente geométrico. | |||

Olhe para o gráfico de <math>f(x) = x</math>. Cada ponto desta função tem a forma <math>(x, y)</math>, onde <math>x = y</math>. Agora o significado gráfico desta equação é que para cada passo que você dá em <math>x</math>, o mesmo passo é dado em <math>f(x)</math>. Em outras palavras, cada unidade para frente é igual a uma unidade para cima e vice-versa. Pegue dois pontos quaisquer com <math>b > a</math>. Temos que <math>\frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} = 1</math>. Vê como a altura <math>f(b) - f(a)</math> e o afastamento <math>b - a</math> são iguais um ao outro? Nós temos um nome para a razão altura / afastamento e é ''tangente''. Você se lembra da escola que a tangente de 45° é 1? Até aqui você pode não saber a definição de uma derivada, mas acabamos de discutir o conceito de taxa de variação, que é a ideia geométrica da derivada. | |||

Por quê <math>f(x) = x</math> é uma linha reta? Porque a sua taxa de variação nunca muda! Sempre é constante e igual a 1. | |||

Revision as of 02:23, 2 August 2022

Para entender poque o gráfico é uma linha reta ou uma curva você não precisa entender cálculo, mas você precisa entender a tangente. Esta página tem por objetivo dar uma ideia bastante superficial dos gráficos. Não vou discutir pontos de inflexão, pontos críticos ou derivadas aqui.

Tudo que você precisa entender para marcar um ponto de uma função no plano cartesiano é entender que cada ponto é um par ordenada da forma [math]\displaystyle{ (x, \ f(x)) }[/math], com [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math] sendo o eixo vertical.

Caso você pergunte sobre a palavra "inclinação". Aqui uso inclinação, tangente e taxa de variação como sinônimos.

Dependendo de qual difícil é traçar gráficos à mão para você, gráficos muito distorcidos podem muito bem levar à interpretações incorretas. Não sei se há professores muito pedantes quanto à "corretude" dos gráficos. Aqui eu comentaria sobre linhas retas x curvas. Algumas pessoas podem ter dificuldade com um ou outro e pode ter relação com a coordenação motora ou algo assim. Mas há tambem uma questão de perfeccionismo onde algumas pessoas podem relacionar a interpretação de alguns problemas de modo muito forçado a um gráfico exageradamente correto.

A parábola

Você já se perguntou por que [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) = x^2 }[/math] é uma parábola? Se [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) = x }[/math] é uma linha reta, como elevar ao quadrado muda tanto? Eu vou recorrer a um raciocínio puramente geométrico.

Olhe para o gráfico de [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) = x }[/math]. Cada ponto desta função tem a forma [math]\displaystyle{ (x, y) }[/math], onde [math]\displaystyle{ x = y }[/math]. Agora o significado gráfico desta equação é que para cada passo que você dá em [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], o mesmo passo é dado em [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math]. Em outras palavras, cada unidade para frente é igual a uma unidade para cima e vice-versa. Pegue dois pontos quaisquer com [math]\displaystyle{ b \gt a }[/math]. Temos que [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} = 1 }[/math]. Vê como a altura [math]\displaystyle{ f(b) - f(a) }[/math] e o afastamento [math]\displaystyle{ b - a }[/math] são iguais um ao outro? Nós temos um nome para a razão altura / afastamento e é tangente. Você se lembra da escola que a tangente de 45° é 1? Até aqui você pode não saber a definição de uma derivada, mas acabamos de discutir o conceito de taxa de variação, que é a ideia geométrica da derivada.

Por quê [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) = x }[/math] é uma linha reta? Porque a sua taxa de variação nunca muda! Sempre é constante e igual a 1.

Now look at [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) = x^2 }[/math]. Take two points where [math]\displaystyle{ b \gt a }[/math]. For example: [math]\displaystyle{ f(1) = 1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(2) = 4 }[/math]. Now take another two points elsewhere, [math]\displaystyle{ f(3) = 9 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(4) = 16 }[/math]. In the first case the rate of change is 1/3. In the second case the rate is 1/7. Every different pair of points that you choose is going to result in a different rate of change. This "proves" that the graph cannot be a straight line, because the rate of change between every pair of points is always different from the rate of another pair. For every step we take in [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math] is going to be the square of the same distance. In other words, as we walk at a constant speed along the x axis, from 0 to infinity, each point of the graph is going higher and higher at even faster speeds. From 0 to negative infinity the same function's behaviour.

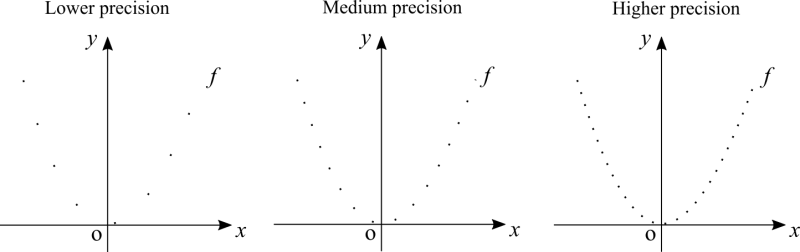

At school you may have learnt that the more points you plot, the more precise your graph is. How does a computer plot a graph? Back at school you may have had already noticed that when the points are very close to each other, connecting two points next to each other with a straight line did resemble a curve. That's how a computer plots a graph, it traces straight lines but because the points are so close to each other, we can't distinguish on screen a dot from a line. Right know you may be unaware of the definition of a limit, but to plot infinitely many points close to each other is the concept of a limit. Computers can't plot infinitely many points though because there isn't infinite time and because we don't need to. Also, screens with infinite resolution doesn't exist.

Now what happens with large, positive and even powers? It's a parabola, but we "flatten" it. The reason for this behaviour is quite simple. For [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt x \lt 1 }[/math] we have fractions and the denominator grows very large with very large powers. When [math]\displaystyle{ x \gt 1 }[/math] the power is so large that the function grows fast enough to become closer to a vertical line.

What about cubics and odd powers? The concept is the same of a parabola with just one difference. For [math]\displaystyle{ x \lt 0 }[/math] the graph goes down rather than up. Remember that the minus sign is kept with odd powers.

Note: In case you noticed that the above graph is slightly distorted compared to the real graph of a biquadratic function for example. I used inkscape to draw a bezier curve and because the software is unable to handle polynomials with a degree higher than cubics, the distortion that you are seeing is exactly the error associated in attempting to trace a biquadratic function using a cubic to approximate it. I've just explained in practical terms one of the fundamental problems that numerical methods have to solve, which is to approximate functions and minimize errors.

The exponential and logarithm

Take [math]\displaystyle{ a^b }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ a, \ b \gt 1 }[/math], for example [math]\displaystyle{ 2^2 }[/math]. You can easily notice that for every unit that you add to the power, the result is even larger. In other words, the rate of change is always changing and thus, the graph cannot be a straight line.

What happens if [math]\displaystyle{ a \lt 0 \lt 1 }[/math]? Then, if we keep increasing the power, it results in smaller and smaller numbers. It's an exponential that decreases for larger powers. The graph is not a straight line because the rate of change keeps changing as we move along it.

What happens if [math]\displaystyle{ a\gt 1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt b \lt 1 }[/math]? Then, from school, we have a root and the graphs of roots are also not a straight line.

The definition of a logarithm relies on the definition of the exponential. When we add the concept of functions we learn that the log and the exp are one the inverse function of the other.

Note: the same comment as above. I used bezier curves to trace the graphs of exponentials and logarithms. It's impossible for a polynomial to perfectly match the exp or log.