Definindo a derivada: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "Antes da discussão eu devo esclarecer uma confusão que aconteceu comigo. Todo livro discute o problema de achar a reta tangente antes de definir a derivada de uma função. Se você já assistiu um vídeo a respeito, quem sabe o clipe ''"[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P9dpTTpjymE| I will derive]"'', você deve ter testemunhado a reta tangente deslizando sobre gráfico da função como se fosse uma montanha-russa. Cuidado aí! A reta tangente é uma coisa. '''A deriva...") |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

[[file: | [[file:derivative_tangent_pt.png|300px]] [[file:derivative_riserun_pt.png|300px]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

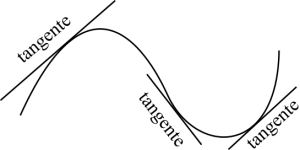

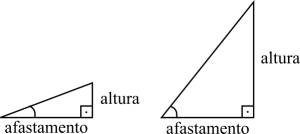

A definição da tangente é a '''razão altura / afastamento''' num triângulo retângulo. Na escola os comprimentos dos lados de um triângulo são dados ou nós medimos com uma régua. Com a geometria analítica sabemos que a distância entre dois pontos, tais que o segmento seja paralelo ao eixo, é <math>|a - b|</math>. Quando a altura é próxima do zero o ângulo é próximo do zero. Isso significa que a rampa tem uma inclinação muito pequena. O oposto é quando a altura é tão exageradamente grande que o ângulo se aproxima de 90°, a maior inclinação possível. | |||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

[[file: | [[file:derivative_secant_pt.png|300px]] <math class="big">\text{tan} = \frac{f(x) - f(p)}{x - p}</math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

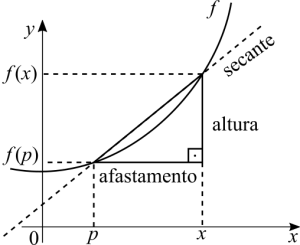

Cuidado aqui! A hipotenusa do triângulo não é a tangente. É uma secante porque esta cruzando o gráfico em dois pontos. Para a fazer a reta secante se tornar uma tangente precisamos de um limite e fazer a distância entre os dois pontos muito pequena. | |||

<div style="text-align:center;"> | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| Line 21: | Line 23: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

O que o limite esta calculando é a inclinação daquele ponto. Se pudéssemos desenhar um triângulo retângulo numa escala microscópica, teríamos a razão altura / afastamento igual àquele número. | |||

''' | '''Nota de rodapé:''' ''sobre a ordem dos pontos. Dependendo do livro a concavidade do gráfico esta para cima ou para baixo. É por isso que a ordem dos pontos no limite acima esta trocada em relação ao padrão, que seria o <math>p</math> à direita de <math>x</math>. Como a notação padrão é <math>f(x)</math> é mais natural escrever <math>x \to p</math> do que ao contrário.'' | ||

==The derivative== | ==The derivative== | ||

Revision as of 20:15, 16 August 2022

Antes da discussão eu devo esclarecer uma confusão que aconteceu comigo. Todo livro discute o problema de achar a reta tangente antes de definir a derivada de uma função. Se você já assistiu um vídeo a respeito, quem sabe o clipe "I will derive", você deve ter testemunhado a reta tangente deslizando sobre gráfico da função como se fosse uma montanha-russa. Cuidado aí! A reta tangente é uma coisa. A derivada de uma função não é a própria reta tangente! Quando calculamos um limite ele produz dois possíveis resultados: um número ou infinito. A definição da derivada é um limite, mas neste caso o resultado é uma outra função. Pode acontecer da derivada resultar num número, que no caso é uma função constante.

Eu menciono esta confusão porque eu acredito que é muito comum as pessoas se enganarem, pensando que derivar uma função é a mesma coisa que achar a reta tangente. Não exatamente. Quando temos funções como polinomiais de um grau maior do que 2 e qualquer função transcendental, o processo de calcular uma derivada produz uma outra função que não é linear. Não é uma linha reta! Não existe o problema de achar uma função que seja tangente a outra em múltiplos pontos.

O problema da reta tangente

A definição da tangente é a razão altura / afastamento num triângulo retângulo. Na escola os comprimentos dos lados de um triângulo são dados ou nós medimos com uma régua. Com a geometria analítica sabemos que a distância entre dois pontos, tais que o segmento seja paralelo ao eixo, é [math]\displaystyle{ |a - b| }[/math]. Quando a altura é próxima do zero o ângulo é próximo do zero. Isso significa que a rampa tem uma inclinação muito pequena. O oposto é quando a altura é tão exageradamente grande que o ângulo se aproxima de 90°, a maior inclinação possível.

Cuidado aqui! A hipotenusa do triângulo não é a tangente. É uma secante porque esta cruzando o gráfico em dois pontos. Para a fazer a reta secante se tornar uma tangente precisamos de um limite e fazer a distância entre os dois pontos muito pequena.

[math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{x \ \to \ p} \frac{f(x) - f(p)}{x - p} }[/math]

O que o limite esta calculando é a inclinação daquele ponto. Se pudéssemos desenhar um triângulo retângulo numa escala microscópica, teríamos a razão altura / afastamento igual àquele número.

Nota de rodapé: sobre a ordem dos pontos. Dependendo do livro a concavidade do gráfico esta para cima ou para baixo. É por isso que a ordem dos pontos no limite acima esta trocada em relação ao padrão, que seria o [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] à direita de [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Como a notação padrão é [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math] é mais natural escrever [math]\displaystyle{ x \to p }[/math] do que ao contrário.

The derivative

We can write the same limit as above in a slightly different notation. The notation emphasizes the idea of a limit more than the geometric idea of the rise / run ratio. [math]\displaystyle{ \text{run} = |x - p| }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \text{rise} = |f(x) - f(p)| }[/math]. Let's call run [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ x \gt p }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) \gt f(p) }[/math] according to the figure above. With run being called [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math], we can write [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) = f(p + h) }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ f'(p) = \lim_{h \ \to \ 0} \frac{f(p + h) - f(p)}{h} }[/math]

The interpretation is that we are making the distance between [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] infinitely small but not equal to zero. This is important, when solving exercises with that definition we can do this [math]\displaystyle{ h/h = 1 }[/math] because we are not dividing zero by zero.

In some places the [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math] is replaced by [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta x }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta h }[/math]. The letter Delta in physics is associated to change or difference, as in [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta S_2 - \Delta S_1 = \Delta S }[/math] in the case of average velocity. It's a another way to write the idea of increments, from one point to the next one.

Footnote: What happened to [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in the above limit? I ended up with [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] just because I was referencing the above figure and didn't want to repeat the same graph.

Leibniz's notation: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dy}{dx} }[/math]. It looks like a ratio, but the meaning of it is not a ratio. If we look at the finding the tangent line problem, the tangent is a ratio that is associated to two points. We have [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(a) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(b) }[/math]. We use those to draw a triangle and view the rate of change as a ratio, because it really is. In physics it's common to associate [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta S/\Delta t }[/math] as velocity, because it's a ratio between variation in space in respect to a variation in time. It's quite fine to associate the derivative with the tangent and a ratio. Centuries ago when Leibniz was developing calculus he probably had the same geometrical perspective.

Now [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{df}{dx} = \frac{d}{dx}f(x) }[/math] has an issue related to the meaning of infinitesimal and we don't learn about this in calculus, unless the teacher takes the time to explain it because it requires knowledge of concepts that are more advanced than the level of calculus. Why can we divide by [math]\displaystyle{ dx }[/math]? Because it represents "infinitely close to zero". Now a function itself is not a number, [math]\displaystyle{ df }[/math] represents a variation from [math]\displaystyle{ f(a) }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ f(b) }[/math] when [math]\displaystyle{ a \neq b }[/math]. The whole problem behind the word "infinitesimal" is that it attempts to convey the idea of the smallest number, which does not exist because every time you have a number, there is a larger and a smaller one. For the same reason, the largest number that is larger than every other doesn't exist too.

I mentioned "to divide" and that [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dy}{dx} }[/math] is not a ratio. Let's make things clear:

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{f(x + \Delta x) - f(x)}{\Delta x} }[/math] (In fact, Leibniz did use the same notation as to divide a number by another because the limit does have a quotient. However, we are dealing with a limit and with limits we have the special case of dividing by something small that is close do zero but it's not zero itself)

When we have a derivative and want to calculate its value at [math]\displaystyle{ x = a }[/math], it's quite fine to associate it to the tangent line problem and the rise / run ratio. The problem is that when we interpret the derivative as a function. A function has two sets, the domain and the range and then the idea of a ratio between whole sets of numbers doesn't make sense.

For second order we write [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d^2y}{dx^2} = \frac{dy}{dx}\left(\frac{dy}{dx}\right) }[/math]. Now this notation is pretty confusing at first because it's not a square, a power. The parenthesis does not mean that we are calculating a product. It means that we are taking the derivative and then again, the derivative of a derivative. This notation is rarely used with single variable calculus, being more common with multivariable functions.

Lagrange's notation: [math]\displaystyle{ f'(x) }[/math]. This notation has an advantage that is to say that the derivative is, in fact, a function. We read it as "f line" but I have no idea if it's a reference to the tangent line. Derive again and we have [math]\displaystyle{ f''(x) }[/math] (f two lines) and we can continue for as many times as we like.

This [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dy}{dx} \Bigg|_{x \ = \ 1} }[/math] means the same as [math]\displaystyle{ f'(1) }[/math].

Newton's notation: [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{x} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{x} }[/math], so on. I have no idea why Newton used this, but it's common in mechanics and other physics related equations.

Differential operator: [math]\displaystyle{ Df }[/math] is called a differential operator. A second order differential is [math]\displaystyle{ D^2f }[/math]. When we calculate a derivative, the process to find the derivative is called differentiation. I don't know functional analysis, but the word "operator" is akin to the arithmetic operations we all know. We add a number to produce another number. We operate with functions to produce other functions.