Completamento de quadrados e a fórmula de Bháskara

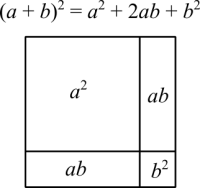

O completamento dos quadrados é melhor entendido com uma interpretação geométrica. Primeiro me permita mostrar a figura:

A associação gráfica é bem clara. O que não fica tão óbvio muitas vezes é o fato de que [math]\displaystyle{ (a + b)^2 }[/math] pode ser visto de maneira literal. Todo o quadrado tem lados cujo comprimento é a soma de dois lados menores[math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] e [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math].

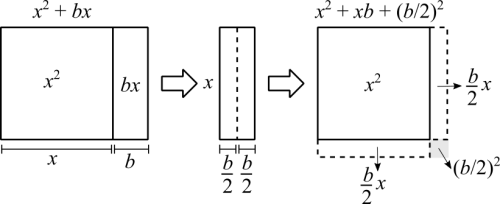

A ideia do completamento dos quadrados é reescrever a equação quadrática na forma [math]\displaystyle{ (a + b)^2 }[/math]. Todos aprendemos na escola que equações quadráticas tem esta forma [math]\displaystyle{ (a + b)^2 }[/math]. Quando [math]\displaystyle{ c = 0 }[/math] fica fácil calcular as raízes porque podemos fatorar a equação na forma [math]\displaystyle{ x(ax + b) }[/math]. Daí resolvemos uma equação linear. Uma equação da forma [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + bx }[/math] é a mesma coisa que [math]\displaystyle{ a^2 + ab }[/math] como a figura acima mostra.

Graficamente temos isto:

[math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + bx + \left(\frac{b}{2}\right)^2 = \left(x + \frac{b}{2}\right)^2 }[/math] (Note que para completar o quadrado aumentamos a área total)

É um pouco engraçado como a maioria dos livros menciona este tópico sem fazer a associação com quadrados. Quadrados, literalmente.

Referência: Eu vi todo este raciocínio gráfico aqui mathisfun (em inglês).

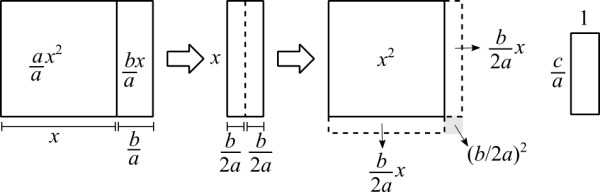

Demonstração da fórmula para resolver equações polinomiais de segundo grau

We can use the process of completing the squares to find a formula to solve quadratic equations. Try to isolate [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ ax^2 + bx + c = 0 }[/math]. You are quickly going to see that, due to the equation having both [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 }[/math], it's going to be hard to achieve it. We really have to rewrite the equation to successfully isolate [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Look back at the previous figure, the only difference between [math]\displaystyle{ ax^2 + bx + c }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + bx }[/math] is that we have a constant multiplying the square (making it larger or smaller) and a lonely constant.

There are other ways to find the formula, to complete the square is one of them.

In the figure [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{c}{a} }[/math] is a rectangle but we don't know it. It could've been a square too.

1st we can divide everything by [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] because if [math]\displaystyle{ a = 0 }[/math] we no longer have a quadratic equation:

[math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x + \frac{c}{a} = 0 \iff x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x = -\frac{c}{a} }[/math]

If we have [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + mx }[/math], can we guess the missing term to have a complete square? It's [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\frac{m}{2}\right)^2 }[/math] because the middle term is always 2 x 1st x 2nd terms. Therefore:

| [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x + \left(\frac{b}{2a}\right)^2 = -\frac{c}{a} + \left(\frac{b}{2a}\right)^2 }[/math] | We did not change the area of the square because both sides of the equation remain equal to each other. To put it into a different perspective. To add a perfect square to both sides of the equation is the same as adding and subtracting the same square to the same side of the equation. |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \left(x + \frac{b}{2a}\right)^2 = -\frac{c}{a} + \left(\frac{b}{2a}\right)^2 }[/math] |

With this we got rid of [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 }[/math] and now it should be easier to isolate [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \left(x + \frac{b}{2a}\right)^2 = -\frac{c}{a} + \frac{b^2}{4a^2} }[/math] |

Apply the least common multiple to the right side. |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \left(x + \frac{b}{2a}\right)^2 =\frac{b^2 - 4ac}{4a^2} }[/math] |

Take the square root on both sides. |

| [math]\displaystyle{ x + \frac{b}{2a} = \pm \sqrt{\frac{b^2 - 4ac}{4a^2}} }[/math] | We can remove the square root from the denominator because it's a perfect square. |

[math]\displaystyle{ x + \frac{b}{2a} = \pm \frac{\sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ x = -\frac{b}{2a} \pm \frac{\sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} }[/math]

Looking back at the figure, what we've just found is a way to express [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in terms of many parameters, the constants in any quadratic equation, such that both sides of the equation are equal to each other. When we began the process of manipulating the equation we had [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to the left side and [math]\displaystyle{ -\frac{c}{a} }[/math] to the right side. The question at that point was: Is there an [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] such that both sides of the equation have the same area?

[math]\displaystyle{ ax^2 + bx + c = 0 }[/math]. If we take a second look at this equation with a geometric perspective, the meaning of it is: we have a sum of squares and rectangles or each term is a number. Is there an [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] such that the sum of two of them is equal to the remaining term in terms of absolute values?

File:Square_complete3.png I'm leaving this error here for reference. The mistake in this reasoning is that the square to the right has an area that is obviously smaller than the initial area to to the left. That's why this reasoning is going to yield a formula that is somewhat similar to the formula that we were looking for, but with some key differences.

Bhaskara's Formula: I have no idea why in Brazil the formula to solve quadratic equations bears that name, while other countries in the world do not make that association with quadratic equations and that Indian mathematician. Another curious fact is that there are two mathematicians with that name and most people don't know that. One lived thousands of years before Christ, the other hundreds of years after Christ.

Completing the cube: one may have wondered if the same procedure can work for cubes. The geometric idea is quite applicable. However, we have to impose a certain condition. The cubic equation must be such that it only has one root, the cubic root.